Empress Eugénie, painted in 1854 by Winterhalter. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

When the wealthy Spanish heiress Eugénie de Montijo, Countess of Teba, met Prince Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, nephew of Emperor Napoléon I and current President of the French Republic, at a state reception in the Elysée Palace in April 1849, she was already considered to be one of the best-dressed women in all of Europe.

Certainly, her unique sense of style and vivid good looks immediately caught the eye of the young President, although at first he rather insulted her by hinting that she should become his mistress rather than his wife. However, Eugénie was undaunted, and when her ardent royal suitor cheekily asked the way to her bedchamber, she instantly responded with ‘Through the chapel, your Highness.’ Their protracted courtship continued for almost four more years until the beginning of 1853, when Louis Napoléon, who had recently been proclaimed Emperor of the French and assumed the title of Napoléon III, finally proposed and was very gladly accepted. Their betrothal was announced on 22 January, and just a week later, they were married in a civil ceremony in the chapel of the Tuileries Palace, followed by an opulent religious affair in Notre Dame Cathedral. Naturally, the stylish new Empress’ wedding ensembles attracted a great deal of attention, with women all over the globe avidly devouring descriptions and drawings of the rose pink taffeta dress she wore to the civil ceremony and elaborate flounced lace and velvet gown made by fashionable dressmaker Madame Vignon for the religious one. Although it was still usual for women to wear eye-catching, colourful dresses to their weddings, Eugènie emulated her peer on the other side of the Channel, Queen Victoria, in opting to wear pure, virginal white on her special day. There was also enormous interest in Eugènie’s opulent trousseau of fifty four dresses, which went on public display in Paris so that her fans could admire such splendid items as a green silk gown trimmed with feathers, a pink watered silk dress trimmed with gold fringe and, most impressively of all, a crimson velvet gown decorated with gold bees and eagles - the symbols of the Bonaparte family that she had just joined.

Fashion magazines, as we know them now, were still in their infancy when Eugènie became Empress of the French, although they were already immensely popular with women (and men) from all social classes. In the 1850s, this perennial interest in fashion was given an extra boost by an intense fascination with the lives of not just Eugènie and Queen Victoria but also the extremely beautiful Empress Elisabeth of Austria. Exquisitely dressed by the finest dressmakers, glittering with fabulous jewels and beautifully immortalised in oils by Winterhalter, these three young women, who formed a trio of close friends, were the indisputable queens of fashion of their times, with enormous influence both at home and overseas. However, of the three, it was undoubtedly Eugènie, with her excellent taste, innate stylishness and passion for luxury goods, who was to have the greatest and longest-lasting effect. Unlike the other two, she had not been born royal and had enjoyed a relatively carefree upbringing with stints at aristocratic boarding schools all over Europe, which had imbued her with a breezy confidence and sense of fun that both Victoria and Elisabeth, conscious at all times of their regal dignity, definitely lacked. This bold self-assurance meant that Eugènie was more than willing to experiment and take sartorial risks that her royal counterparts did not dare to contemplate. Then, as now, it was considered beneath the dignity of royalty to appear too fashionable, with royal ladies cultivating a certain splendid dowdiness. Eugènie, however, who came from rather less exalted stock, felt free to be as modish and up to date as she liked - enabled both by proximity to the always fashionable shops of Paris and by her husband, Napoléon III, who was only too happy to encourage her extravagance.

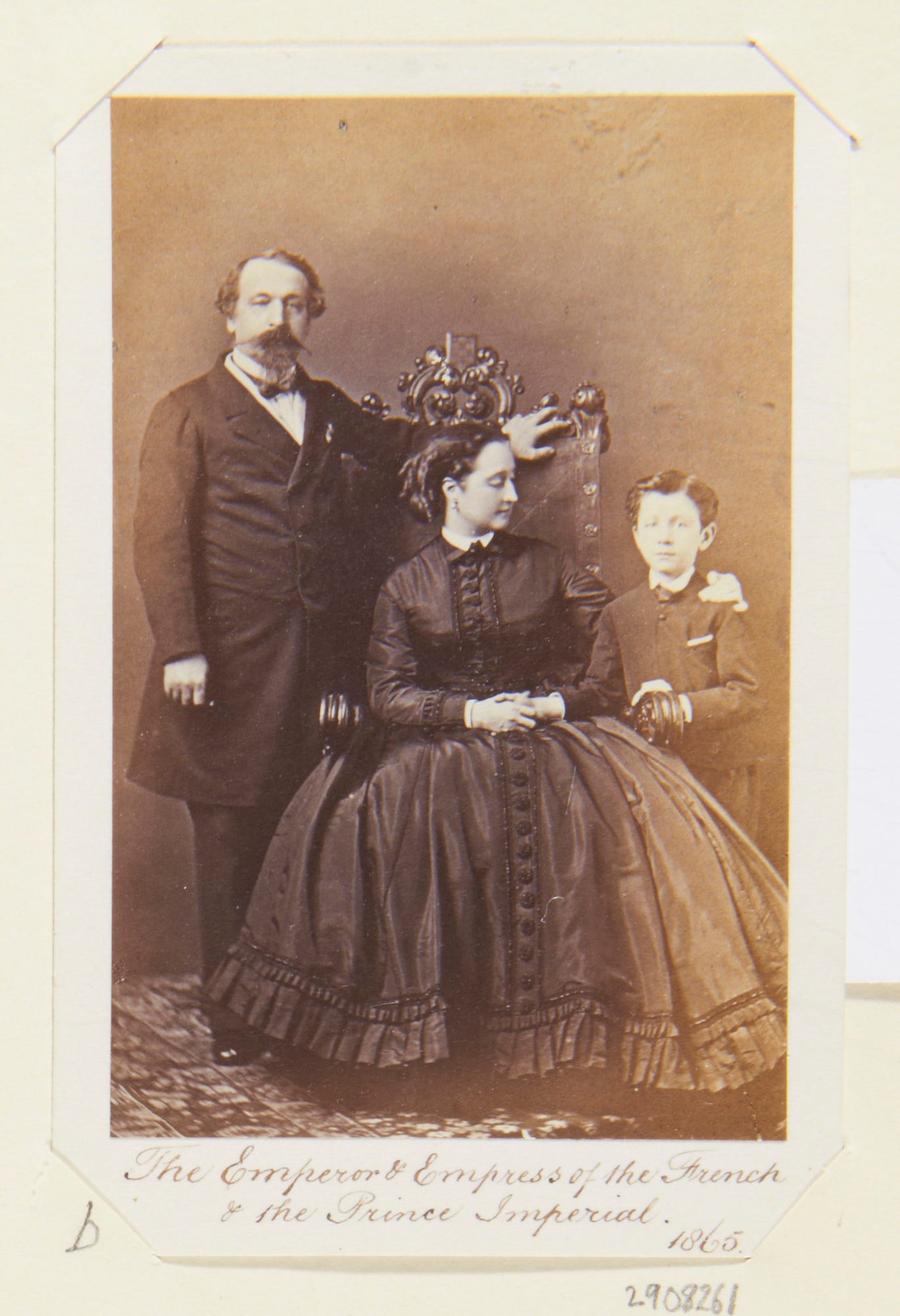

Napoléon III, Eugénie and their son, the Prince Impérial, photographed in 1865. Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2025.

As well as being the nephew of Napoléon I, Eugènie’s husband was also, thanks to the complicated lineage of the Bonaparte family, the cherished grandson of Napoléon’s first wife, Empress Joséphine, and as such had been imbued since childhood with a healthy respect for stylish women. As his uncle had realised fifty decades earlier, one of the easiest ways for a fledgling imperial court to gain respect both at home and internationally was to be as magnificent as possible - a lesson that Napoléon III took very much to heart, even to the extent of emulating his uncle’s highly restrictive edicts that court ladies should only ever wear white to evening receptions, in Eugènie’s case often bedecked with her favourite lilacs or trailing ivy, and should never be seen in the same dress twice. Luckily for Eugènie, she had an enormous allowance, 1,200,000 francs a year, to pay for all of this excess, much of which was spent on her clothes and accessories. The Empress’ enormous collection of garments was carefully looked after in large rooms in the attics of the Tuileries, where her dresses were kept in massive wooden wardrobes. Whereas Marie Antoinette had famously selected her day’s outfits by sticking pins in a book of fabric samples taken from her gowns, Eugènie’s orders for the day, which might well encompass anything up to four outfit changes, were transmitted via a speaking pipe installed in her dressing room, which was connected to the wardrobe rooms upstairs. The Empress’ maids would then scurry about, gathering the requested items and using them to dress four mannequins which had been made with Eugènie’s exact measurements and which would then be sent down to the dressing room in a specially constructed lift, which had been made wide enough to accommodate the Empress’ voluminous skirts without crushing the precious fabrics and lace. Once in the dressing room, which was simply furnished with a lace and ribbon-decked dressing table and mirrored alcove, Eugènie and her ladies would decide what jewels and accessories would look best with the dress.

The promenade in the Galerie des Glaces, Versailles on 25 August 1855 during Queen Victoria’s visit to Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie. Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2025.

While her husband looked back to Napoléon I for inspiration, Eugènie was completely fascinated by Marie Antoinette, who had been her predecessor in the French royal palaces, even inhabiting the same rooms. At Versailles, she was thrilled to be presented with the Petit Trianon, Marie Antoinette’s hideaway in the palace park, and spent vast sums restoring it to its eighteenth-century glory and furnishing the rooms with items that had once belonged to the guillotined Queen. She even had herself painted on at least two occasions in gowns and poses that were deliberately reminiscent of Marie Antoinette, most famously the Winterhalter portrait that depicts her in a sweeping gown of yellow, blue and white silk, with her auburn hair powdered white and dressed in a rococo style. Like Marie Antoinette, Eugènie had a passion for exquisite jewellery, flamboyant dresses and being the absolute centre of attention whenever she ventured out. Also like her predecessor, she completely understood the importance and power of a perfectly put together outfit, recognising that part of her role as Empress was to act as an unofficial ambassadress for France and its industry, which meant being immaculately turned out in the very finest French goods at all times and showcasing the latest Parisian fashions to dazzling effect. Tall, willowy and, unlike Marie Antoinette, genuinely beautiful with stunning red-gold hair and lovely blue eyes, Eugènie was any fashion designer’s dream client and was one of those fortunate women who look good in pretty much anything.

Detail from Winterhalter’s portrait of Empress Eugénie as Marie Antoinette. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Although she took her role as an ambassador for French industry very seriously, Eugènie’s favourite designer, Charles Frederick Worth, was actually an Englishman who had quickly attracted her attention shortly after establishing his fashion salon in Paris in 1858. Determined to attract attention from aristocratic patrons, Worth had employed the method of creating cut price dresses for the fashionable society hostess Princess of Metternich, charging her just 300 francs per gown in exchange for the valuable exposure that she gave to his work - a strategy that was richly paid off when Eugénie admired a Worth ballgown that the Princess was wearing and demanded that she introduce her to her dressmaker the very next morning. The association between Worth and Eugènie, both of them so absolutely devoted to fashion, was a match made in heaven and continued until the designer’s death in 1895, during which time he designed the vast majority of her clothes and together the pair exerted a powerful and some might say absolute influence over the fashions of the era, dictating everything from the most stylish colours to the length and width of skirts. It was thanks to Eugènie and Worth that the crinoline began its gradual decline from an elaborate, ungainly hoop to the more compact bustle, while hemlines on day dresses were slightly raised to allow women to walk more freely - this last innovation inspired by Eugènie’s passion for long walks and loathing for getting her hems muddy. Thanks to his association with Eugènie, Worth became the most celebrated designer in all Europe with his salon at 7 Rue de la Paix becoming one of the hottest addresses in town, patronised by all the wealthiest and most stylish women in the world and cementing Worth’s reputation as the father of haute couture, which surely makes Eugènie if not its mother then certainly its fairy godmother.

Empress Eugénie painted by her friend Queen Victoria at Osborne House on 9 August 1857. Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2025.

Although Eugènie had already been considered exceedingly well dressed before she met Worth, her style blossomed afterwards and became even more bold and experimental. Memoirs of the period are full of descriptions of Eugènie’s fabulous clothes, from the tilted feathered bonnets she wore to the races to the striped petticoats, worn beneath flounced skirts, she favoured one summer season at Fontainebleau. Every detail of her clothing was avidly scrutinised, discussed and then copied by women all over the world, who enthusiastically seized upon such pieces of information as the precise shade of blue that Eugènie most favoured, assisted by the wonderful new shops springing up in Paris at this time, all part of her husband’s grand designs for his capital city. Along with Baron Haussmann, who had been handpicked to oversee the renovation of central Paris, Napoléon III created the sweeping, elegant boulevards, beautiful parks, opera house and huge department stores that visitors to the French capital enjoy today and which served as a mecca to the fashionable and rich during its heyday in the 1870s. The opening of Printemps, an enormous and beautiful department store on the new Boulevard Haussmann, in 1865 completely revolutionised the way that women shopped and made access to fashion and luxury goods easier than ever before now that they were sold beneath the same roof, making it possible to buy an entire outfit at the same time without hopping from shop to shop. One of the new luxury brands was Louis Vuitton, which was founded in Paris in 1854 and patronised by Eugènie, who commissioned them to make the expensive monogrammed luggage necessary to transport her enormous wardrobe from place to place. Another was Tiffany, which was founded in New York in the 1830s but exhibited their wares at the Paris Exposition of 1878 - Charles Lewis Tiffany, the founder was so enamoured with Eugènie’s sense of style that he based the distinctive hue of the Tiffany packaging, now known as Tiffany Blue, upon the Empress’ favourite colour.

Empress Eugénie, painted in 1855 by Sir William Ross. Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2025.

Eugènie’s own taste in jewels was remarkably simple, although she certainly enjoyed wearing beautiful pieces for state occasions, usually having older royal jewels, such as those worn by Empresses Joséphine and Marie Louise, the consorts of Napoléon I, remounted in more contemporary settings. On her wedding day, she wore a spectacular pearl and diamond tiara, which formed part of a set commissioned by her new husband as a wedding present and which incorporated gems previously worn by Marie Antoinette’s daughter, the Duchesse d’Angoulême, as well as Empress Marie Louise’s pearls. Although Eugènie particularly favoured pearls, no doubt because they emphasised the creamy perfection of her complexion, like a lot of redheads, she also adored emeralds, and they appear several times in inventories of her jewellery collection. Although Eugènie’s jewellery collection included some truly spectacular pieces and was rumoured to rival even that of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia (who would later become a close personal friend), perhaps her most favourite piece was a small gold pin topped with an emerald four leaf clover, which she had won as a prize in a lottery organised by Napoléon III, who was then her fiancé, at Compiègne before they were married. Touchingly, Eugènie treasured this relatively modest piece for the rest of her life, wearing it every day even with the most elaborate dresses and alongside her more splendid jewels.

A bejewelled bouquet holder given by Eugénie to her friend Queen Victoria during a visit to Paris in August 1859. Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2025.

Although rouge and other cosmetics had been commonly worn by women from all classes in the eighteenth century and was indeed a requirement for anyone who intended appearing at the French court, where women were expected to sport perfectly matching red circles of rouge on their cheeks, by the time Eugènie became Empress of the French, obvious cosmetic use had been abandoned by the higher echelons of society and associated only with women of dubious virtue such as actresses, artists models and prostitutes. In Victorian England, even the tiniest touch of colour on the lips and cheeks was considered highly daring, with women employing stealth in order to enhance their looks. French women were rather less inhibited but even so excessive cosmetic use was still frowned upon - until Eugènie came on the scene with her bold and not at all subtle Spanish style of making up her face, which involved pencilling in her eyebrows, colouring her eyelids blue, rouging her lips and cheeks and using rice powders by Bourjois, Guerlain and other companies to perfect her ivory complexion. She is even credited with the invention of solid block mascaras, which enabled her to lengthen and darken her eyelashes - as a natural redhead, it’s likely that she needed a little bit of extra oomph. Eugènie was very proud of her hair, which was usually arranged in an extremely becoming style known as ‘à l’imperatrice’, and used henna imported from overseas to keep it bright - a practice that was naturally copied by less naturally favoured women, making auburn hair exceedingly fashionable in the latter half of the nineteenth century. There were also rumours that not content with the brightening effects of henna, Eugènie also liked to scatter real gold powder through her tresses to make them even more eye catching, although this was denied by some of her contemporaries, no doubt keen to make it clear that she was not as foolishly extravagant as her predecessor Marie Antoinette, who was accused of similar frivolities. What cannot be disputed however is that Eugènie took a healthy interest in the art of making the most of herself, patronising all the best and most exclusive Parisian cosmetic companies and making no secret of her reliance upon carefully applied artifice, which was in itself an innovation in a period when women who used make up were expected to do it so subtly.

A copy of Winterhalter’s 1861 portrait of Eugénie, which she gave to Queen Victoria. Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2025.

One of Eugènie’s favourite companies was the House of Guerlain, which had been founded on the Rue de Rivoli in 1828 and made its name supplying the royalty and aristocracy of Europe with fine fragrances. Eugènie had a serious passion for perfume and was one of Guerlain’s best customers - when she developed migraines, she asked them to develop a special lemon and bergamot cologne that she could dab on her temples. The result was Eau de Cologne Impériale, which was Guerlain’s first cologne and a made-to-measure fragrance and is still sold by them today in a bottle decorated with Bonaparte bees. Another favourite perfume company was Creed, which started life in London in 1760 as a tailoring company. Eugènie originally favoured them because of their beautifully cut riding habits, which had long been a staple in any fashionable Parisian lady’s wardrobe, but also loved their fragrances. Their perfume, Jasmine Imperatrice Eugènie, was commissioned for her as a present from her husband and is a warm and sensual vanilla, bergamot and amber oriental scent that perfectly matched the Empress’ personality and remained a favourite until her death in 1920 at the age of ninety-four.

Empress Eugénie in front of Saint-Cloud, painted in 1856 by Edouard Boutibonne. Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2025.

The glorious empire of Napoléon III and his Empress Eugènie fell apart in 1871, less than ten years after it began. Threatened by a mob advancing upon the Tuileries palace, in an eerie repeat of the events of August 1792, Eugènie was forced to call upon the assistance of her dentist in order to escape. She only had time to pack a small valise with belongings before being whisked away to England and safety, shortly to be joined by her husband and young son. Although much of her wardrobe, which had once been the most envied in all Europe, was packed up and sent to her in England, most of it was left behind along with most of her jewels, which were deemed to be the property of the French people. Although Eugènie remained a byword for French chic for a couple more years to come, she went into mourning after the death of her husband in 1873 and then lost all remaining interest in fashion after her young son was killed in action in 1879. When a curious noblewoman paid the former Empress of the French a visit several years later, she was very much struck by sad contrast between the wizened, carelessly dressed and even rather dowdy elderly woman who greeted her and the serenely beautiful and exquisitely dressed young Empress depicted surrounded by her bevy of equally gorgeous ladies in waiting in the huge Winterhalter portrait that hung in a prominent position in the entrance hall. ‘One could hardly believe that it was the same woman,’ she concluded sadly, reflecting on the vagaries of fortune and tragedies that had blighted the life of this once supremely elegant woman, the last survivor of a long vanished golden age.

I had no idea she was so influential! Granted, I knew very little about her going into this piece. But the connection between her and Worth and their huge influence on fashion blew my mind!